|

|

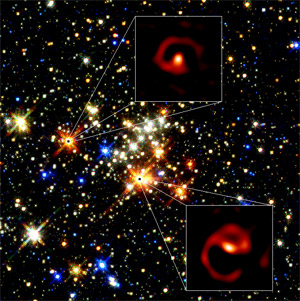

The Quintuplet cluster with two of its stars magnified to show their spiralling shape. Image: Peter Tuthill |

SYDNEY, 18 August 2006: Bursting with firey red brilliance, the stars of the Quintuplet cluster have been found to be surrounded by 'pinwheels' or spirals of cosmic dust using a technique dating from 100 years ago.

The Quintuplet cluster, consisting of five bright red stars and a haze of hundreds of others, is one of the biggest star clusters situated near the centre of our galaxy (within 100 light years). It showcases some of the most massive stars ever known, that shine far brighter than our own Sun.

Peter Tuthill, co-author of the study published in today's edition of Science and astrophysicist from the University of Sydney, Australia used images from the world's biggest telescope, the 10-metre Keck, to zoom onto two of the five Quintuplet stars. Tuthill used a very unusual approach by reinventing an idea called aperture masking, which dates back more than 100 years.

"It took a lot of persuasion to get the experiment going, because in science often technology is out of date even a few years down the track, so I was doubly thrilled when we were able to make the best images ever taken by using this antique approach," said Tuthill.

An astronomical research team led by Tuthill showed that the Quintuplet stars are surrounded by spiral plumes of dust called pinwheel nebulae. The beautiful spirals of glowing hot dust are found around certain very rare massive stars called Wolf-Rayets, named after the two astronomers who first discovered them.

"Wolf-Rayets represent a key phase in the life cycle of a massive star. It is the last step before the star explodes as a supernova," said Tuthill.

The pinwheel nebulae surrounding these Wolf-Rayets comes about because the stars are in a binary system, with two stars orbiting each other. Both are creating powerful stellar winds. A standing shock wave is produced where these winds collide and material is swept into the wake behind the binary system.

A sooty carbon dust from the wind is formed in the shock region and flows into this wake away from the stars. This hot glowing plume is then wrapped into a beautiful spiral by the orbital motion of the binary star.

"You can see the same geometry in the stream from lawn sprinklers: each droplet of water is going in a straight line, but the rotating spigot creates a spiral pattern," explained Tuthill, who has been studying these dusty spirals ever since they were first discovered in 1999.

The amazing pinwheel nebulae in the Quintuplet were almost overlooked as the data was collected by Tuthill several years ago at the Keck telescope, but was filed away because at first it did not appear to contain anything of interest.

Early this year when he analysed the data more carefully, Tuthill realised the data at longer wavelengths - which are better for viewing stars embedded behind lots of obscuring dust - could be used to recover the beautiful images.

So what do the stars hold for the future? "Studies like this one, and a number of follow-up experiments I am planning at telescopes worldwide, give us a unique new window into the dressing room as the star prepares for its final cataclysmic performance," said Tuthill.